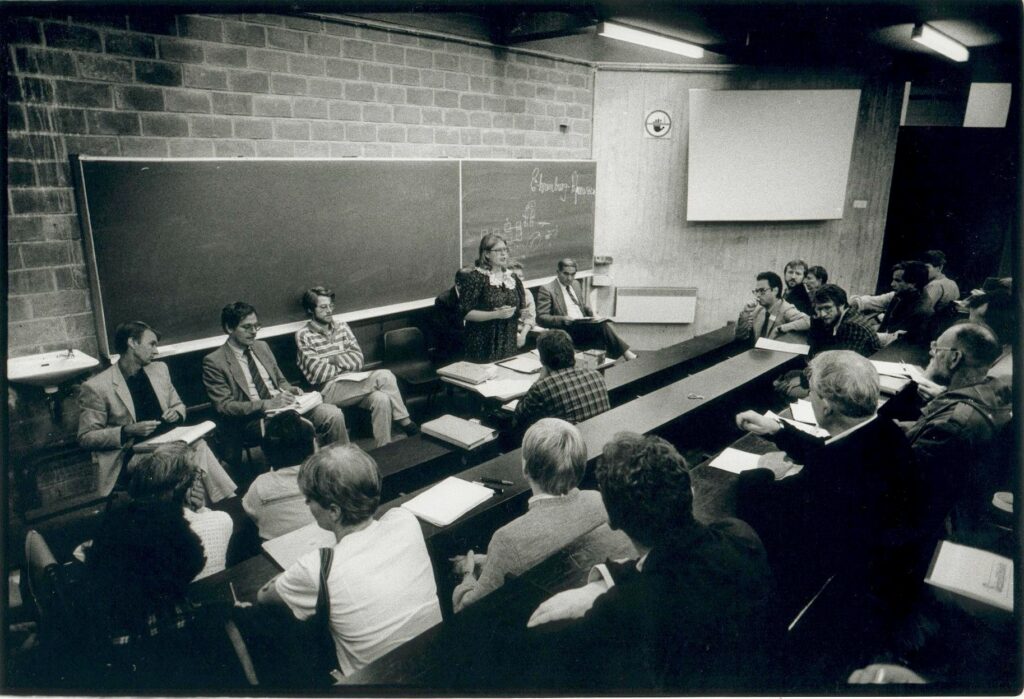

Image: BIEN founding conference, Louvain-la-Neuve, September 1986. Facing the lecture room, from left to right: Bill Jordan, Claus Offe, Philippe Van Parijs, Nic Douben, Annie Miller, Greetje Lubbi, Riccardo Petrella

Basic Income Earth Network has made a crucial contribution to the worldwide awareness of the idea of an unconditional basic income. For this to happen, perseverance was key. But also technology.

Philosopher Philippe Van Parijs reflects on current events and debates in Brussels, Belgium and Europe

A striking — and moving — initiative was taken last month by the executive committee of the Basic Income Earth Network (BIEN). They wanted to meet BIEN’s founders, or at least those of them who were still alive and who they could trace. The first question that came up was how the founders managed to find one another. Good question. In pre-internet times, this was not a straightforward matter. Nor was the running of an international network.

The idea of a universal, unconditional income had occurred to me in December 1982, as a clever way of addressing the problem of structural unemployment without relying on endless growth. I called it “allocation universelle”. The idea was so clever, I thought, that it must have occurred to others before me. How can I find them? Long before Google search, tips from colleagues were the best bet.

It did not take long for a friend at the OECD to send me a working paper published in 1979 at the University of Aston (UK) under the title “Can a social wage solve unemployment?”. The name was different, but the idea was the same and the argument similar. I immediately wrote to the author, a certain Stephen L. Cook. Alas, the letter came back. The addressee had just died, and his paper did not contain a single reference. Later tips proved more fruitful. They led to a Dutch trade union leader, a Capri-based Swedish aristocrat, the editor of a French magazine defending a “social income” since the 1930s and a handful of others.

I sent them all a personal letter inviting them to “the first international conference on basic income”, which was held in Louvain-la-Neuve in September 1986. Most of the participants did not know of one another beforehand, but their convergence and enthusiasm far exceeded what was needed for the wish to create an association to emerge. The Basic Income European Network was born, with an irresistible acronym: BIEN.

But then the real work had to start. A network cannot exist without a newsletter. In English only, we decided, but with the firm resolve to minimize the under-representation of what was written or happening in other languages: not an easy job. Three times per year, the newsletter had to be printed, stapled, slipped into an envelope on which a stamp had to be stuck before the pile of newsletters was taken to a post box. To cover the cost, an annual membership fee had to be collected, often in cash and by post so as to avoid prohibitive (pre-euro) bank charges.

A network cannot thrive without personal meetings. Every two years, BIEN organized a conference. Announcement, programme and registrations were sent by (quite often unreliable) post. In most cases, if you wanted copies of your paper to be available to other participants, you had to print them yourself and bring them along in your suitcase. And before the rise of low-cost flights, traveling to the conference could take a long time.

Despite all these logistic hurdles, BIEN reached the 21st century with more and more newsletter subscribers and conference participants coming from outside Europe. They soon started a campaign for turning BIEN into a global network. Forget it, was my first reaction. Operating on a European scale was already overstretching our modest human resources. Moreover, it seemed to me that an unconditional basic income could only make sense in countries with a developed welfare state. On both counts, I was proved wrong.

Firstly, the rapid spread of internet made it possible to reach a fast-growing number of BIEN members very cheaply by e-mail, to send them the newsletter electronically and to set up a website. The idea of a viable global network was no longer ludicrous. Secondly, in January 2004, Senator Eduardo Suplicy, chief campaigner for the globalization of BIEN, managed to convince president Lula to sign a law that committed Brazil to the gradual introduction of a universal basic income. I attended the ceremony — and capitulated.

In September 2004, at its 10th congress held in Barcelona, BIEN became the Basic Income Earth Network. Since then, it has done far more than just survive. It now has affiliate networks in 30 countries, runs a website with tens of thousands of visitors and has switched to organizing a congress every year rather than every two years. The next one, for the first time in hybrid format, will be held in Brisbane, Australia.

All this is due in the first place to a wonderful succession of executive committees made up of committed and competent volunteers, not least to the committee currently in charge, which the founders had the pleasure to meet last month. But technology also play an important part in the story. Just one final example.

Where did I attend last month’s meeting? In a car driven by my wife on a French motorway, with one of my grandsons taking part in his own way from the back seat. I could not only hear, but also see on a screen I held in my hands both my fellow founders and our successors, the latter in places as far apart as India, California and Japan. Totally unimaginable when we founders first met 36 years ago. Mind-boggling.

(This text was originally published in The Brussels Times, Wednesday, 17th August 2022. We share it here with kind permission by the author Philippe Van Parijs.)